NOTE

The information contained in this document represents information about preview features of the product. Features might change when the product is released for general availability.

Writing Rules with Gaia Declarative C++

Gaia rules are written in Declarative C++. Gaia Declarative C++ differs from traditional C++ in several ways:

- Declarative rules cannot be called directly. Instead, they are invoked by the Gaia system in response to changes to the database. In traditional C++ your code determines the order of execution. When you write Rules in Gaia Declarative C++, the Gaia platform determines the execution order of Rules

- In a Rule, Gaia Declarative C++ can reference tables and fields within the database as well as local variables. You do not have to declare types that are in the database. Field references do not have type declarations in a Ruleset; the translation engine supplies these from the Schema definitions in the database. Gaia converts the fields that you reference into code-based accessors.

- The Gaia system passes system contexts to the Rules context from which you can access related rows. These are:

- data context: you are handed the exact row that changed so you are working on the relevant data.

- navigation context: you can navigate to related data in other tables relative to the data context.

Because the Rule functions are invoked by the Gaia system, you are automatically operating on the data that caused the change.

- Since Gaia knows the type of relationship that exists between tables, it can automatically generate iteration over M rows in a 1:M relationship.In the case of a one-to-many relationship, referencing a related table can result in iteration over all of the rows related to the parent data context. Depending on the relationships in your schema, a field reference can return 0,1, or multiple rows. Because the Rule functions are invoked by the Gaia system, you are automatically operating on the data that caused the change.

- Gaia Declarative C++ rules are multi-threaded by default. Each Rule is scheduled to run on a thread in a configurable thread pool and each thread runs in its own transaction. The Gaia system takes care of the synchronization of data in the database for you.

- Note: While Gaia Declarative C++ doesn’t prohibit the use of global static variables, we recommend against it due to added overhead that you incur ensuring that your code is thread safe.

- The Gaia tools translate the Declarative C++ code to traditional C++ code based on what Gaia knows about your data as represented in the Gaia Catalog. This means that you don't have to hand-write traditional data access and navigation code.

In Gaia, Rules and rows are directly connected. In a Rule, data that resides in the Gaia database are field references. Field References in the Rule look like variables, but they reference fields in rows of the database; there is no need to declare them as variables. When data changes in the database, Rules that reference the data execute automatically.

In addition to the Ruleset level declarations, you can declare any number of local variables at the start of a specific Rule using standard C++ syntax, such as int BagCount. Local variables are scoped to the Rule that they are defined in.

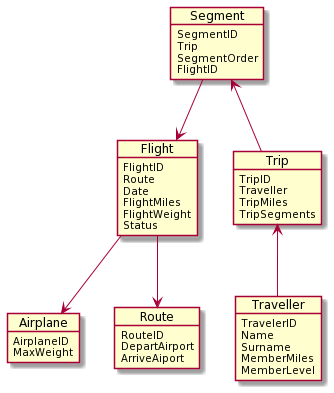

Picture an application that manages airplane flights, passengers, and baggage. There is a table that tracks actual flights. At the end of each flight, the unique row for that flight has a field called FlightMiles to reflect the miles flown in the flight. In another table, there is a row for each traveler reflecting MemberMiles.

Let’s start with four simple rules based on the following schema:

Member Rule 1

// Update the number of miles the member has flown

{

MemberMiles += @FlightMiles;

}

The key to understanding this Rule is that FlightMiles is designated as an Active Field. Whenever a change to that field is committed, the Rule engine automatically fires the Rule.

Each flight has many passengers. There is a 1:many relationship between the Flight row in the database, which contains FlightMiles, and the Traveler row, which contains MemberMiles. The rules engine recognizes that relationship from the Catalog and automatically iterates this statement in the Rule for every passenger on the flight. So, that one assignment causes the system to:

- Recognize that there are many passengers on the flight.

- Finds all the passengers on this flight; the Rule then iterates over the result set.

- Starting from the Flight row, navigate to the correct Traveler row in that table for each passenger. Even here, the rules engine is automatically navigating through several intermediate rows to get from Flight to Traveler.

- Complete the update for every passenger. Navigation paths execute against sets of rows completely transparently and automatically.

Member Rule 2

// Update member status

{

if ( @MemberMiles > 75000 ) { MembershipLevel = Silver };

}

In this example, MemberMiles is an Active Field. The rules engine automatically fires the Rule each time MemberMiles changes. Rule 1 changes the value of the field and causes the rules engine to fire Rule 2. This is referred to as Forward Chaining which we discuss further in the next section.

We track each trip in a table called Trips which has a counter for TripSegments. How do we know a segment is complete? One answer could be to add a field in Flights called FlightLanded. Then we could write:

{

if (@FlightLanded) { TripSegments +=1}

}

Before moving on, let’s examine what is taking place with both of these conditional statements. A flight segment was completed. An Active Field caused the rules engine to fire a Rule. That Rule relates to a particular row for a particular flight. That row, in turn, is related to many Trip rows. Not only that, the path from the flight row to the appropriate trip row involves navigating through an intermediate segment row. We start with a simple one statement conditional and end up with:

- Code is generated to locate all segment rows that are related to the flight row.

- The Rule is fired once for each of the many hops between airports (segments) associated with this flight.

- The system navigates through the segment row in each case, which fires the event to update the SegmentsFlown.

Now consider the baggage that is loaded onto the plane. The baggage is scanned and the loaded baggage weight is tracked in a table.

// Track weight of baggage loaded on flight

on_insert(BaggageLoadScan)

{

FlightWeight += Weight

}

In this case, the Rule is defined using the on_insert prefix.

// Check for overweight situation and raise the alarm

{

If (@FlightWeight > MaxWeight )

{ ActivateWeightAlarm(FlightWeight) }

}

Since rules are written with statements which are, at their core, C++ statements, you can call functions that perform external actions from the body of the Rule. The first Rule uses a C++ utility function which tracks the weight of the baggage loaded on the flight. This procedural utility could also update the database, which would in turn trigger the execution of Rules.

Through Forward Chaining, the rules system fires the second Rule each time the value of FlightWeight changes. If the value of FlightWeight exceeds the maximum allowed baggage weight, the Rule calls the ActivateWeightAlarm method, which is a C++ function that can be external to the rules declarations.

Forward chaining

When the value of a field reference changes in the active database, Gaia fires the Rule automatically. As rules get fired, they might also change fields, and any active field changes can, in turn, fire other rules. We call this process Forward Chaining. The combination of rules firing automatically, making changes, then cascading to the execution of other rules is the basis for our declarative system.

Sometimes when a field’s value changes, a Rule fires against the individual row. In other cases, though, a Rule might update fields in many rows. For example, after a flight lands, all the luggage might be marked as arrived. The rules engine generates the underlying query for the Navigation Path to make this work automatically. This is a key part of eliminating control flow.

One of the fundamental results of Forward Chaining is that the order in which Rules execute is determined by the order in which commits that contain changes to active fields occur.

The power derives from the fact that there is no need to create queries, navigate through tables, copy, and map data: Gaia handles all of that automatically.

Transactions

Transactions are complex to think about in a world with forward chaining since cascading rules, particularly across multiple Rulesets and authors, a transaction could go on forever. For this reason, the Gaia platform focuses on the use of transactions to ensure the consistency of operations within the scope of each Rule.

The rules engine automatically brackets every Rule with a Begin and Commit Transaction sequence. As each transaction is committed, Forward Chaining fires subsequent Rules. All forward chaining takes place after the transaction is committed.

When a transaction aborts, usually due to a conflict with another transaction, the aborted Rule is automatically rescheduled for execution by the Rules Engine. For example, two concurrent transactions might change the same field value. In this case, the first one to commit 'wins,’ and the second one must re-execute.

In the declarative system, rules based on field changes are the only mechanism for moving from one Rule to the next; there is no explicit control flow. A single Rule, particularly if it has multiple statements, might cause several other rules to fire.

Parallelism

Gaia automatically fires all rules in parallel by default. This is made possible by the Rules Engine’s managed execution environment and the implementation of transactions in the database itself.

Important: Be careful when using objects that have a shared mutable state, such as static variables. There are no protections to prevent all the usual race conditions, timing, and visibility issues common in procedural programming. In short, all multithreading best practices apply when dealing with procedural code.

There are two mechanisms available to control this behavior. Primarily you can add the SerialStream(stream-name) attribute to a Ruleset to force all rules in that Ruleset to execute in a serialized fashion. Be aware that even when run serially, the ordering is not deterministic, e.g. the scheduler does not perform any type of sorting on the pending rules-to-be-run. It might be worth explicitly stating that.

Rules in Rulesets with a common stream-name never run in parallel with each other. Be aware that serialized rules are not guaranteed to run in the same hardware thread; this means that writing code that relies on data persistence is not recommended. To put it more fundamentally, thread local storage is not guaranteed to work and should not be used inside rules. For applications requiring a single-threaded approach, you can specify the number of threads that Gaia uses to process rules. To guarantee single-threaded semantics are applied, set thread_pool_count to 1 in the gaia.config file. If a transaction fails due to a concurrent transaction exception, the rules engine retries the transaction. You can configure the global setting for the number of retries for a transaction. Note that this setting is global and applies to all transactions in the database. To specify that Gaia should not retry transactions, set rule_retry_count to 0.

Nested Iteration

In a Rule, statements that contain references to fields in the database can initiate iterative behavior over the returned result set. Gaia iterates through all indicated values (based on the reference) until the statement has exited, either by running out of values or it is forced to exit via a 'break' or 'return' statement, before proceeding to the next statement in the Rule.

The Rules translator translates statements that generate loops from left to right with each successive loop executing within the scope of the previous loop.

Suppose we have an if statement that iterates over all passengers, which references the luggage for each passenger.

If ( @passengerstatus == “missing” )

{ if ( luggagestatus == “loaded” )

{ . . . } }

Here we have a loop within a loop. The entire statement is executed once for each passenger. Then, while focused on that passenger, the inner if is executed once for each piece of luggage that belongs to the passenger.